A widely anticipated report by the Senate intelligence committee into torture committed by the Central Intelligence Agency has a hole at the center of its story: the men the CIA tortured.

Lawyers for four of the highest-value detainees ever held by the CIA, all of whom have made credible allegations of torture and all of whom remain in US government custody, say the Senate committee never spoke with their clients. In some cases the Senate’s investigators never attempted to speak with the men whose abuse is at the heart of what the committee spent over four years investigating.

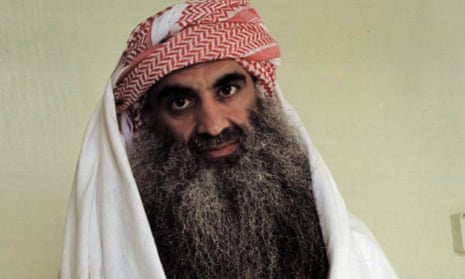

The absence of the torture victims’ accounts calls the thoroughness of the Senate committee inquiry “directly into question”, said David Nevin, who represents accused 9/11 architect Khalid Sheikh Mohammed.

“If you’re conducting a genuine inquiry of a program that tortured people, don’t you begin by talking to the people who were tortured? It seems here, as far as my client is concerned, no effort was made to do that.”

The four suspected al-Qaida members not interviewed by the committee received some of the CIA’s most brutal treatment: Mohammed and his 9/11 co-defendant Walid bin Attash; accused USS Cole bomber Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri; and Abu Zubaydah. All four men are among the 142 men who remain in US military custody at Guantánamo Bay.

The Senate torture investigation, spearheaded by the committee chairwoman, Dianne Feinstein of California, has come under criticism before for not conducting interviews – from the CIA, which has argued the committee’s lack of interest in talking with officials involved in torture reveals the forthcoming report to be a hatchet job. The committee has shot back that the CIA’s extraordinary spying on its investigators, for which its director, John Brennan, issued a public apology, was an attempt at a coverup that provoked a constitutional crisis.

Beset from all sides, the report concludes that the agency’s post-9/11 interrogations, detentions, and renditions were less effective and more brutal than it portrayed to the Bush administration and Congress. Republicans on the committee consider it a witch-hunt. Senate Democrats are furious with the CIA and the White House, which have for months held up declassifying portions of the report.

Human rights organizations consider the release of sections of the report, expected in December, to be a watershed moment for holding the CIA accountable for torture. Yet lawyers for the men the CIA tortured consider the committee’s omissions consistent with years of US efforts to conceal the truth about the program and insulate those involved from reprisal – including from an ongoing inquiry by an allied country that once hosted a secret CIA prison.

“It’s apparent to me that the United States government has absolutely no desire to credibly investigate or in any other way hold accountable the people who tortured my client,” said Cheryl Bormann, a Chicago attorney who represents Bin Attash.

The Senate committee, through Feinstein’s spokesman, Tom Mentzer, declined to comment.

The torture experienced by the four men was among the harshest the CIA administered. Mohammed, Nashiri and Zubaydah are the only three men the CIA has acknowledged waterboarding – Mohammed 183 times, and 83 times for Zubaydah; Nashiri, believed to have been waterboarded two or three times, was also threatened with a gun and a power drill. At a secret prison in Poland, according to a leaked report from the International Committee of the Red Cross, agency officials would douse Bin Attash with buckets of cold water and wrap his frigid body in plastic sheeting before interrogations.

While the Senate intelligence committee opted not to speak to the men, the Obama administration actively blocked an investigation by US ally Poland into CIA torture committed on its territory.

As documented by the European Court of Human Rights this summer, Polish investigators repeatedly sought permission from the US to interview Nashiri and Zubaydah. Their attorneys, Amrit Singh and Joe Margulies, said the US denied those requests.

“The US government doesn’t allow Abu Zubaydah to communicate with anyone, even through counsel, unless they approve the content. I can’t tell you or anyone else what Abu Zubaydah tells me about his torture,” Margulies said.

A stranger tale of investigative obstruction unfolded earlier this year at Guantánamo. Bormann’s co-counsel for Bin Attash, US air force captain Michael Schwartz, was approached by what he can only identify as an “investigator for a foreign country” in February, seeking to interview their client. In April, Bin Attash wrote a brief, 10-line letter to the investigator signalling his cooperation, and then, as Guantánamo detainees must, submitted it to a government classification review.

The review determined in June that even though the contents of Bin Attash’s letter contained no classified information, the letter could not be sent to its intended recipient, lest it reveal unspecified classified information. Bormann and Schwartz counteroffered to send it “to whom it may concern”, but were rebuffed.

“What we often are told is, you can take Unclassified Fact A and you put it together with Unclassified Fact B, you can have a classified fact,” Schwartz said.

Representatives for the Justice Department, the CIA and the Defense Department did not respond to a request for comment about detainee access for the foreign investigation.

No CIA interrogator, official, supervisor or policy official has ever been prosecuted for torture; only a CIA contractor has. The Justice Department’s special prosecutor for CIA torture did not interview at least 11 ex-CIA detainees, and ended his four-year inquiry in 2012 without charging anyone. The CIA official, known as “Albert”, who revved the drill at Nashiri got a post-retirement contractor job with the agency to train its operatives, the AP reported in 2010.

The Senate’s inquiry is not a criminal investigation, nor is it likely to lead to criminal charges. Its concern is the veracity of information the CIA presented about its programs to the Bush administration and Congress.

Andrea Prasow of Human Rights Watch said that while she would prefer the detainees’ stories were told, the Senate committee report was “still incredibly important” for uncovering the truth about CIA torture.

But Margulies, Zubaydah’s attorney, said the lack of Senate interest in speaking with the men the CIA tortured indicated a continued US resistance to reckoning with an episode Feinstein in April called a “stain on our history”.

“One might have hoped that an inquiry into torture by the CIA would have included a conversation with the people the CIA tortured,” Margulies said.

“The investigators skipped this step because they evidently believe, like the torturers before them, that these men have no voice worth hearing. We have not come as far as we think.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion